The Yijing ( or I Ching) is the ancient Chinese Book of Changes. It is made of 64 chapters called Hexagrams. The book’s elusive and poetic lines have inspired musicians, writers, and artists alike. On this page, we’ve gathered some of the best stories of musicians who’ve drawn inspiration from this timeless text.

Some are rumors, while others are heartfelt tributes—each offering a unique connection to the Yijing.

All of the music cited in this article can be found on this playlist:

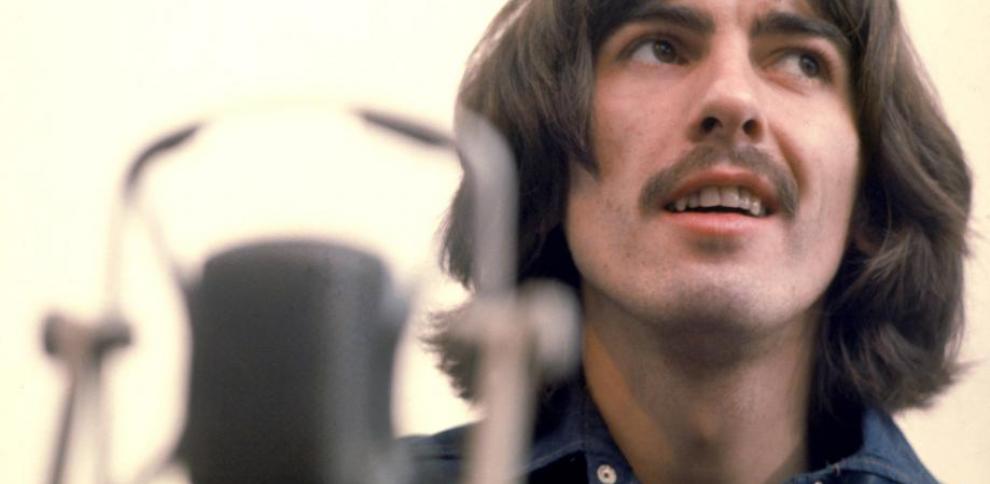

George Harrison

In 1968, a boy from Liverpool, fresh from his travels in the East, searching for inspiration, pulled an old Chinese book off the shelf and opened it at random.

“It seemed to me to be based on the Eastern concept that everything is relative to everything else, as opposed to the Western view that things are merely coincidental. […] The Eastern concept is that whatever happens is all meant to be … every little item that’s going down has a purpose. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” was a simple study based on that theory … I picked up a book at random, opened it, saw “gently weeps”, then laid the book down again and started the song.”

~ George Harrison 1

Was George Harrison inspired by the Yijing when writing one of the Beatles’ most iconic songs from the White Album? It’s possible, but the narrative surrounding this connection might be misleading, as he could have been referencing a different book altogether. After some research, I couldn’t pinpoint exactly which edition of the Yijing or hexagram George might have encountered. There’s no mention of “gently weeps” in the major translations. Could it have been Hex 57 ䷸ Proceeding Humbly (Wind over Wind, also known as Gentle over Gentle)? Or perhaps a blend of different lines from different hexagrams?

Handwritten lyrics of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”2

In this article, Allyn Gibson suggests that George might have been talking about Hex 61 ䷼ Innermost Sincerity , more specifically the third line that reads:

六三 得敵。或鼓或罷。或泣或歌。

Liù sān dé dí. Huò gǔ huò bà. Huò qì huò gē.

Six in the third place means: He finds a comrade. Now he beats the drum, now he stops. Now he sobs, now he sings. (Wilhelm translation)

While this is a possibility, we may never know for certain. However, it would not have been the first time that line inspired someone to make music.

Chick Corea

Interestingly enough, in that same year, 1968, the renowned jazz musician Chick Corea has embraced that very same line from hexagram 61 as the title for both his song and album. A typical Yijing-related coincidence.

“The title Now He Sings, Now He Sobs comes from I Ching, an ancient Chinese book that I was into in the ’60s when I was studying different philosophies and religions. It’s also known as the “Book Of Changes.” And it has a section named “Now He Sings; Now He Sobs — Now He Beats The Drum; Now He Stops.” The poetry of that phrase fit the message of the trio’s music on Now He Sings, Now He Sobs to me. You know, the gamut of life experiences — the whole human picture and range of emotions.”

~Chick Corea3

It might seem strange to see such a spike in interest in the Yijing during that time. Could it be mere coincidence? I don’t think so. I suspect it’s more likely due to the release of the latest edition of the Wilhelm and Baynes translation that came out in 1967. Then again, it was the sixties—a time when the quest for meaning sparked a lively exchange of ideas between East and West.

But there is yet another song inspired by the Yijing from that same period.

Pink Floyd

Back to the UK, we may want to check Pink Floyd’s 1967 track Chapter 24, from their debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. It takes its name and lyrics directly from Hex 24 ䷗ Turning Back (Receptive over Thunder, also known as Return).

The time is with the month of winter solstice

When the change is due to come

Thunder in the Earth, the course of heaven

Things cannot be destroyed once and for all

The specific version of the Yijing they reference is unknown, though it is likely an adaptation of Wilhelm’s translation.

The lyrics were written by Syd Barett. The line “The movement is accomplished in six stages” is clearly just the instructions of the Yijing while drawing the six lines. More details about the lyrics can be found here.

Bob Dylan

Another musician that most certainly crossed paths with the Book of Changes is Bob Dylan. In 1974, the Nobel laureate released Idiot Wind, where he briefly mentions a consultation with the I Ching. Lend your ears to his wonderful performance:

I ran into the fortune-teller, who said beware of lightning that might strike

I haven’t known peace and quiet for so long I can’t remember what it’s like

There’s a lone soldier on the cross, smoke pourin’ out of a boxcar door

You didn’t know it, you didn’t think it could be done, in the final end he won the wars

After losin’ every battle

It’s a very long song, with incredible sarcastic lyrics.

In the article Bob Dylan and the I Ching, Steve Marshall mentions of a bootleg version of the song that has an even more explicit connection to the book, replacing that first verse with:

I threw the I-Ching yesterday, it said there’d be some thunder at the well.

The article suggests that this might be a reference to Hex 51 ䷲ Taking Action (Thunder over Thunder, also called Shock) changing to Hex 48 ䷯ Replenishing, also known as The Well (Water over Wind).

Gilberto Gil

So far we’ve seen musicians that had a few chance encounters with the Yijing. Now to the experts.

I’m talking about the Brazilian musician Gilberto Gil, who was a great admirer of the Book of Changes.

He recounts that before starting the commemorative project (tour and album) Tropicália, he consulted the I Ching and received hexagram 35, which advises: an enlightened ruler and an obedient servant are the requirements for great progress. Gil recognized in it his role as the “obedient servant” and surrendered himself to what he calls the “sweet leadership” of his friend Caetano [Veloso].

~ Interview for Audio News.4

Gil appreciated the Yijing so much, a few hexagrams are featured in some of his album covers:

The lines for Hex 22 ䷕ Adorning (Mountain over Fire) can be seen on the blue stripes over the moon next to the title in Luar (1981). A year later, in Um Banda Um (1982), on the top left side we can see Hex 1 ䷀ Initiating (Creative over Creative). On the bottom left side of Diadorim Noite Neon (1985) there is Hex 56 ䷷ Travelling (Fire over Mountain), which is, incidentally, made out of the swapped trigrams of Hex 22.

Diz o I Ching

Divino é saber

O que distingue

Você de você

Você dos outros

Do outro você

Você do mundo

Do você do serThe I Ching says

Divine is knowing

What distinguishes

You from you

You from others

From the other you

You from the world

From the you of being

UAKTI

While we’re in Brazil, we must not miss Uakti, the influential Brazilian instrumental group. Known for their unconventional musical instruments, Uakti was led by Marco Antônio Guimarães, who designed and built many of the unique instruments used in their performances. In the late 80s and early 90s they gained international recognition, performing in Japan, Europe and collaborating with Philip Glass in Águas da Amazônia.

In 1993, they released Music for the I Ching, conceived by Marco around the hexagrams and trigrams of the Yijing. Each track is dedicated to a different trigram, along with three additional pieces: “Dance of the Hexagrams,” “Alnitak” (named after a star in Orion’s Belt), and “Point of Mutation.”

More than simple homages to the trigrams, Uakti’s album was composed taking into account each of the trigram’s design, incorporating the lines and experimenting upon them as sounds.

The eight trigrams [and 64 hexagrams] of the Chinese classic serve as rhythmic operators. The continuous lines of the trigrams correspond to a long note (quarter note), while the broken lines are translated into quick notes (eighth notes). The instruments proliferate the combinatorics in a suite5

Alexandre Campos Amaral Andres dissects the complex musical composition for the album in his master thesis, which can be read here (in Portuguese).

John Cage

This list would not work without mentioning him. Just like Uakti, John Cage harnessed the hexagrams to generate music directly from the Yijing.

His renowned work, Music of Changes, intricately weaves the principles of the Book of Metamorphosis into its composition. The chance operations dictate the music.

For this work, Cage employed I Ching-derived chance operations to create charts for the various parameters, i.e. tempi, dynamics, sounds and silences, durations, and superimpositions. With these charts, he was able to create a composition with a very conventional manner of notation, with staves and bars, where everything is notated in full detail. The piano is played not only by using the keys, but also by plucking the strings with fingernails, slamming the keyboard lid, playing cymbal beaters on the strings, striking the keyboard lid, etc. […] This work may be seen as the first step of Cage’s voyage into the world of chance composition. […]However, chance here only applies to the process of composition. The actual result, or composition, that derived by these means, along with the performance, are fixed and determined, things which Cage would also later abandon in subsequent compositions7

The result is some of the most unique pieces of music you’ll ever hear:

While this may not sound as lyrical or soothing as other genres, and it might even be a bit jarring to the ears, there’s a rawness and intensity in Cage’s work that challenges our perceptions of what music can be. It invites listeners to engage with sound in a different way, in the boundaries between music and noise. In this context, I can’t help but recall something he once said:

“When I hear what we call “music”, it seems to me that somebody is talking. But when I hear the sound of traffic I don’t have a feeling that someone is talking, I have a feeling that sound is acting.”

~John Cage (watch here)

Read more about his Music of Changes here.

Joni Mitchell

I’d like to close the list with this gem.

In a homage to Amelia Earhart, the Canadian singer Joni Mitchell wrote “Amelia”, comparing the vapor trails from jet planes to the all unbroken lines of the first hexagram: Hex 1 ䷀ Initiating .

I was driving across the burning desert

When I spotted six jet planes

Leaving six white vapor trails across the bleak terrain

It was the hexagram of the heavens

It was the strings of my guitar

Amelia, it was just a false alarm

I hope you’ve enjoyed this selection.

If you know of any other musicians inspired by the Yijing, I’d love to hear about them in the comments!

Here are some honorable mentions:

…With one hand on the hexagram

And one hand on the girl

I balance on a wishing well

That all men call the world…Stories of the Streets by Leonard Cohen.

…God is a concept by which measures our pain

I don’t believe in magic

I don’t believe in I-Ching

I don’t believe in Bible…God by John Lennon.

…I am the Bible and the I-Ching

The red, the white and the blueWhy do you ask me a question?

Asking is not going to show

That I am all things in existence

I am, I was, I go...Gita by Raul Seixas.

Facing the morning, wearing her shadow

she throws her dice and I-Ching

success in Japan, a rescuing man

knows she won’t change anythingNo Secrets by The Angels.

Dead Prez – Lets Get Free (2000) has the hexagram 8 Multitude on the cover.

Further reading:

- Source: The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8. ↩︎

- ‘I Me Mine – The Extended Edition’ ↩︎

- Source: The Making of Chick Corea’s Now he Sings, Now he Sobs ↩︎

- Source: Acervo Pessoal de Gilberto Gil ↩︎

- Source: GIRON, Luis Antônio. Uakti faz primeira turnê pelo Brasil. Fôlha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 22/04/1994. Capa da Folha Ilustrada ↩︎

- Photograph by Irving Penn / © 1947 (Renewed 1975) Condé Nast Publications Inc. ↩︎

- Source: https://johncage.org ↩︎